Colonoscopy and CT colonography are the two principal modalities for detecting bowel disease. Colonoscopy is essentially a camera passed through the bowel to visually inspect the bowel, take photographs, flush it clean and take biopsies or remove polyps. CT Colonography (CTC) is a CT scan of the bowel allowing radiological pictures of the bowel to be taken after a small tube is inserted into the rectum to inflate the bowel with gas and dye. As you can imagine, both procedures are a bit awkward and a bit uncomfortable for patients. CTC is sometimes arranged by a GP or by a Specialist, rather than recommending a colonoscopy. This decision might arise from difficulty accessing a specialist or accessing a colonoscopy in the public system. If both tests are available to you, then you might well wish to have a say in that decision or at least have an understanding of what guided your doctor’s recommendation. This article helps you to understand the procedures and the nuances of this important choice.

Diagnostic Yield and Accuracy

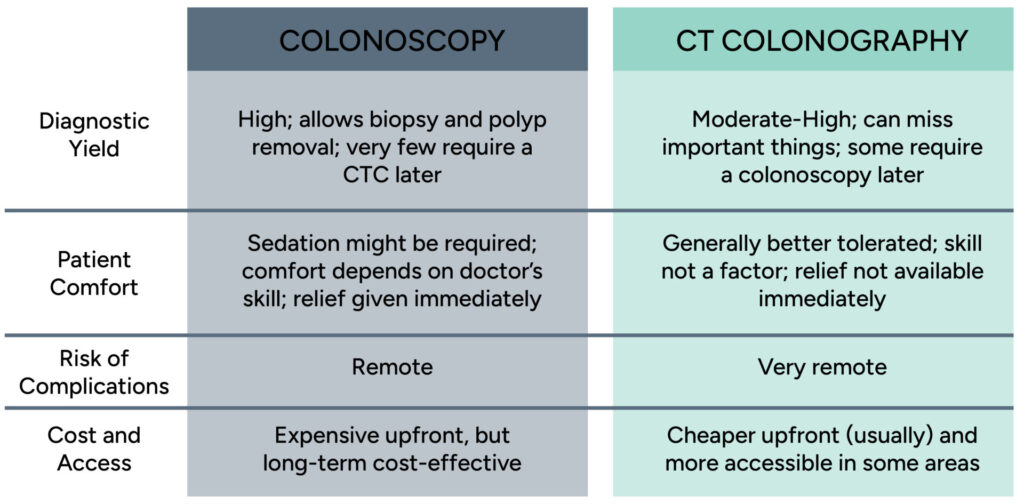

Colonoscopy is considered the gold standard for detecting bowel disease. It is very reliable at finding polyps of any size in the bowel and at seeing areas of inflammation. CTC is not as good at finding polyps and certainly cannot see more subtle areas of inflammation. Consider the analogy of a CT scan being able to see sunburn on your skin – it simply can’t. In expert hands, colonoscopy should detect at least 98% of polyps which are larger than10 mm in size (and it often picks up polyps of just 2-3mm). It also allows removal of the polyps painlessly, there and then. CTC demonstrates a sensitivity of only 85-93% for polyps >10 mm but is even less effective for flat or small lesions (<6 mm) and nothing can be done about them if they are detected by the CT. It will miss mild inflammation and flatter polyps, some of which – like serrated polyps – are higher risk polyps for turning cancerous.

Approximately 8–14% of patients undergoing CTC will have findings that necessitate a follow-up colonoscopy anyway e.g. for polyp removal or biopsies. This follow-up requirement may reduce the overall efficiency and cost-effectiveness of a CTC. It is fair to say that about 2-3% of colonoscopies fail to provide a complete inspection, in which case the patient has to go for a CTC instead, so it’s possible that both modalities have to come to the help of the other.

In certain clinical scenarios a CTC is a very good choice and is arguably preferable to a colonoscopy. This includes patients for whom sedation is unsafe or for patients who have symptoms in the abdomen that aren’t necessarily from the bowel alone. The CTC takes in images of the surrounding organs too and thus provides an overall view of what is happening in the abdomen.

Missed Pathology

CTC may miss smaller or flat polyps and cannot biopsy tumours or remove polyps during the same examination. A landmark study by Pickhardt et al. (2003) reported that CTC had limited sensitivity for lesions smaller than 6 mm, missing approximately 65% of these diminutive polyps. Furthermore, a metaanalysis by de Haan et al. (2011) found that CTC detected only 56% of flat lesions compared to 92% with colonoscopy. Consider the repercussions of this: being told that your colon is OK when in fact 1 in 3 times that information is false and the polyps continue to put you at risk of bowel cancer later. Colonoscopy, while more sensitive, is not infallible; a systematic review by Rex et al. (2015) reported a miss rate of approximately 2-6% for adenomas larger than 10 mm, often attributable to factors such as poor bowel preparation, incomplete examination, or operator variability. Tandem colonoscopy studies, in which a patient has two colonoscopies on the same day by two different endoscopists, also confirm that there is variability in polyp detection between endoscopists. In other words, choose your endoscopist carefully! You can read more about how to do so in my other articles.

Complications and Harm

Colonoscopy carries a risk of gastrointestinal perforation, with rates estimated at approximately 0.06% (6 patients per 10000 procedures) according to a large-scale study by Rabeneck et al. (2008), which analysed over 97,000 colonoscopies. Bleeding that requires action after a polyp has been removed occurs in about 0.2–0.6% of cases, particularly in patients on anticoagulant medication. Sedation-related adverse effects, including cardiopulmonary complications, occur in 0.1–0.3% of procedures, most commonly among older adults or those with comorbid conditions (Wexner et al., 2001).

CT colonography, by contrast, has a significantly lower risk of perforation, with rates below 0.02% (2 patients per 10 000 procedures) as reported in the ACRIN National CT Colonography Trial (Johnson et al., 2008). However, CTC involves ionizing radiation, with an effective dose typically ranging between 2 to 6 millisieverts (mSv) (Sosna et al., 2006). This radiation dose translates into a very small – but not a zero – lifetime attributable risk of getting a cancer because of this radiation. That risk is estimated at approximately 1 in 10,000 for a single CTC, according to Brenner and Georgsson (2005). Repeated examinations, particularly in younger individuals, may increase this cumulative risk. Additionally, sometimes the CTC finds incidental non-bowel things that warrant yet further CT imaging and hence even more radiation.

Patient Comfort and Preferences

CTC is generally better tolerated due to its less invasive nature, shorter procedure time, and lack of sedation. However, both require a period of dietary restriction and then bowel preparation beforehand, aspects which many patients regard as the worst aspect of CTC and colonoscopy. Both modalities involve something being inserted into your rectum too, which remains a psychological barrier for people. Studies suggest that patients who undergo CTC report higher satisfaction scores, particularly among first-time screeners (Halligan et al., 2015). The 8-14% who had to also go through a colonoscopy because something was seen in the bowel might not be so satisfied if you questioned them later! In a study by van Gelder et al. (2012), mean pain scores (on a 0–10 scale) were reported as 1.7 for CTC and 3.7 for colonoscopy, indicating greater discomfort associated with colonoscopy. Pain during colonoscopy was more pronounced in unsedated or lightly sedated patients, while CTC discomfort was primarily due to gas stretching the bowel.

You can view this problem of pain from another perspective: if you have pain during a CTC you cannot be administered any pain relief by the radiographer or radiologists, but pain during a colonoscopy can be helped straight away. As mentioned earlier, selecting your endoscopist is very important because skilled endoscopists typically have very satisfied and very comfortable patients most of the time.

Cost and Economic Considerations

Colonoscopy is costlier per procedure (typically $3500-$4500 in New Zealand) but may be more cost effective long-term due to its therapeutic capability (it removes the polyps). If you have health insurance, this isn’t really your problem anyway, but if you finance your colonoscopy yourself, it is an important consideration. Doctors tend to charge more if multiple polyps need to be dealt with or if large and complex polyps are discovered that need specialised techniques to remove them. Only about 2% of patients under a skilled endoscopist’s care need a CTC afterwards because the examination was incomplete. CTC on the other hand is less expensive upfront (typically $1500 in New Zealand) and it may be beneficial if you are self-funding the scan. In population-level screening programs where colonoscopy resources are limited (Heitman et al., 2010) it might be a good economic choice. But for the 8-14% of patients who have to go through a colonoscopy after a CTC, especially if you are self-funding your care, this could mean a “double hit” to the finances. Your insurance status, your financial position and where you live clearly influence the decision on CTC or colonoscopy.

Professional Guidelines and Recommendations

- AGA (American Gastroenterology Association): Recommends colonoscopy as the preferred method for CRC screening; CTC is an acceptable alternative if colonoscopy is contraindicated or declined.

- BSG (British Society for Gastroenterology): Endorses colonoscopy for high-risk populations; CTC may be used when colonoscopy is incomplete or not tolerated.

- ESGE (European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy): Recommends colonoscopy for diagnostic and therapeutic needs; supports CTC as a secondary option.

- ACS (American Cancer Society): Recommends colonoscopy every 10 years or CTC every 5 years starting at age 45 for average-risk individuals.

- ASGBI (Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland): Acknowledges colonoscopy as the standard, but encourages CTC in select cases, including frail or elderly patients.

- SAGES (Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons): Highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic superiority of colonoscopy but recognises the role of CTC in tailored screening approaches.

- ACR (American College of Radiology) Appropriateness Criteria: Supports CT colonography as an appropriate and effective screening option for average-risk individuals who are unwilling or unable to undergo colonoscopy.

- AGA (American Gastroenterological Association): Recommends colonoscopy as the preferred method for CRC screening; CTC is an acceptable alternative if colonoscopy is contraindicated or declined.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Colonoscopy vs. CT Colonography in self-funding patients

In conclusion:

Colonoscopy remains the most definitive modality for the diagnosis of bowel diseases and it allows intervention for abnormalities that it detects. It is referred to by most organisations as the “Gold Standard” test, with CTC usually ranking as perhaps the “Silver Standard” by comparison. Both procedures are safe and well tolerated when performed by skilled doctors. Many factors should be considered by your referring doctor before selecting which test is most suitable for your situation. You are encouraged to understand these nuances and be involved in the decision on whether colonoscopy or CT Colonography is best for you.

References

- Pickhardt, P. J., et al. (2003). “Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults.” New England Journal of Medicine, 349(23), 2191-2200.

- Johnson, C. D., et al. (2008). “Accuracy of CT colonography for detection of large adenomas and cancers.” New England Journal of Medicine, 359(12), 1207-1217.

- Halligan, S., et al. (2015). “Patient acceptability and diagnostic accuracy of CT colonography compared with colonoscopy for investigation of patients with symptoms suggestive of colorectal cancer.” BMJ, 350, h166.

- Heitman, S. J., et al. (2010). “Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk North Americans: an economic evaluation.” PLoS Medicine, 7(11), e1000370.

- American Gastroenterological Association. (2020). CRC Screening Guidelines.

- British Society of Gastroenterology. (2019). Colorectal Cancer Guidelines.

- European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. (2020). Colorectal Screening Recommendations.

- American Cancer Society. (2018). Colorectal Cancer Early Detection Guidelines.

- Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. (2021). CRC Screening Position Statement.

- Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. (2022). Best Practices in Endoscopic CRC Screening.