Many patients are curious about polyps in the bowel and like to understand a bit more about them. Our focus as bowel specialists is often centred on finding and dealing with polyps when we are performing a colonoscopy procedure and patients wonder what these are and why there is such intense focus on them. My explanation below is aimed at a basic understanding of what a polyp is and how these are critically important to preventing bowel cancer.

What is a polyp?

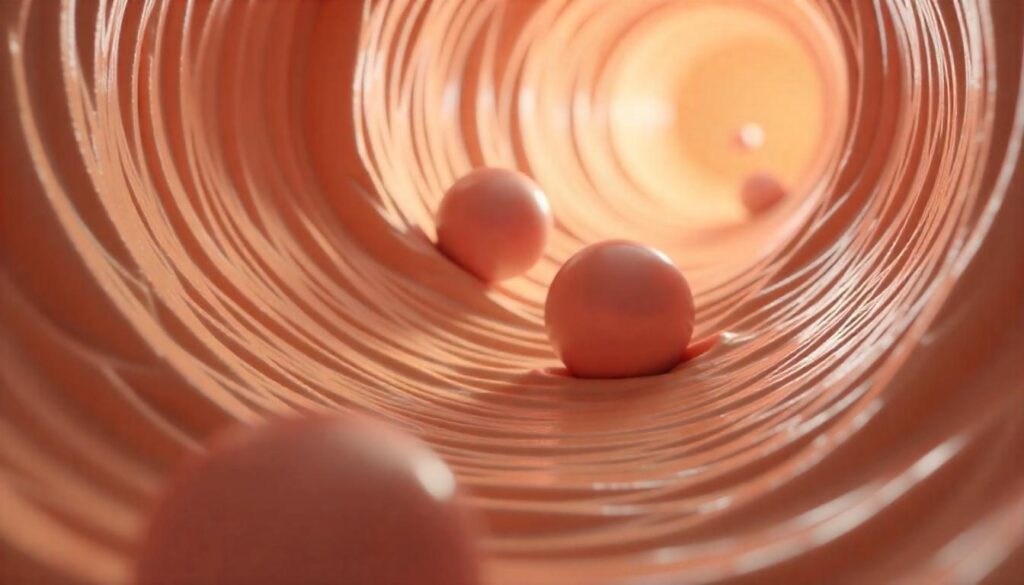

A polyp is a growth created by a cluster of cells growing from the lining of the bowel. These growths protrude into the cavity of the bowel and are spotted during a colonoscopy whilst the camera navigates through the bowel. We could liken the growth of polyps from the bowel lining to the growth of mushrooms in a pine forest. My image of this might help you to imagine polyps growing and the terminology we use to describe them. If we observed a flat mushroom on the ground, this would equate to a “flat” polyp growing on the surface of the bowel lining. Such a mushroom might barely rise up from that forest floor, but it clearly looks very different to the pine needles. If we instead observed a rounded mushroom standing a few centimetres tall on our forest floor, this would equate to a polyp in the bowel that we call a “sessile” polyp. A mushroom growing with a little stalk would equate to a polyp that we call a “pedunculated” polyp. Just as happens with mushrooms growing in a forest, the size of the mushrooms can vary considerably in height and width. Mushrooms also vary in texture and colour, so it will come is no surprise to you that polyps can do likewise.

This growth of cells from the lining of the bowel happens due to a combination of circumstances. Every day your cells of your body go through the natural ageing process and when cells reach the end of their lifespan they die and are replaced by new cells. This of course happens inside the digestive system with millions of cells being shed every day. Up to 80% of the bulk of faecal material is in fact dead cells, dead organisms or old mucus, with just 20% comprising food residue. This program of cell growth is regulated by DNA in our genes. Usually this program runs smoothly and a healthy cell replaces an old one. Just as with computer programs, sometimes the cellular program does not run as it should. This results in abnormal growth of the cell which may multiply to become visible to the human eye. It is estimated that 40,000 cell divisions occur before this could be visible to the human eye as a polyp.

The ageing process is one of the commonest reasons why the DNA code develops flaws in it. Sometimes the DNA code has a flaw in it that was inherited from your ancestors, predisposing you to the development of polyps from the day that you were created. We know of many documented flaws that are inherited and which are linked to the development of bowel polyps. Only a small percentage of patients who grow polyps harbour such known flaws. For most of us, these are random flaws that occur and we just get unlucky in making a polyp. It has been recognised that things that we do to our bodies increase the chance of such flaws occurring. These include smoking, obesity, high carbohydrate diets, consumption of red meat, processed foods, preservatives, nitrates and possibly disturbance to our gut microbiome (healthy organisms that reside in our digestive system). Polyps are benign growths i.e. they cannot penetrate into the body and spread. If they did so, we would not call them benign but “malignant”. Bowel malignancy is otherwise known as “bowel cancer” or “colorectal cancer”.

Why do polyps matter?

Polyps arise because of unstable DNA programs in the cell. The polyps tend to grow over time and some of the polyps go through further unstable changes as they grow. These changes are called “dysplasia” and range from mild to moderate to severe. If this process of dysplasia change continues, the polyp eventually becomes a cancer. It is usually a slow process of transformation from a benign polyp into a cancer: Typically this is a 5 to 7-year process but it varies according to the species of polyp. Almost every bowel cancer begins its life as a benign polyp. If we can find polyps that are still benign and remove these from the colon, we can prevent bowel cancer from occurring. There is a window of opportunity to do so, but it begins to close the longer that the polyp is present inside you.

If there is a history in your family of relatives growing bowel cancers or polyps, this heightens the risk that you have inherited the genes that have caused them to have this trouble. The more relatives that you have that have these problems, the closer they are in lineage to you and the younger they were when they were diagnosed each heighten the prospects of you harbouring polyps or having bowel cancer in your lifetime.

How do we deal with polyps?

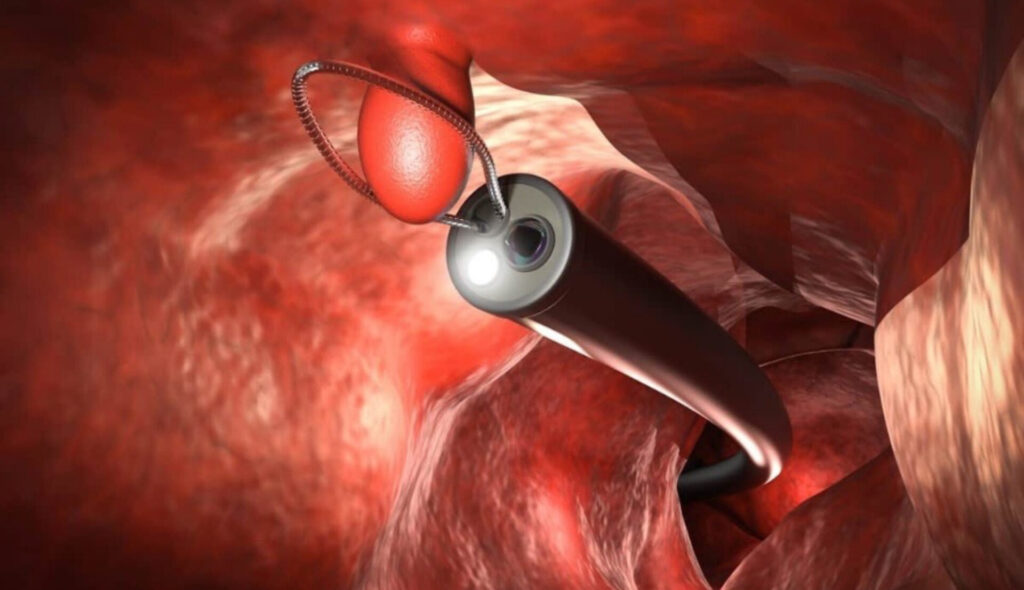

Polyps are spotted during a colonoscopy either by the doctor’s keen eyes, or by nurses who are watching the screen with us, or (in some endoscopy facilities) by artificial intelligence built into the camera. The polyps are documented for their location, size, shape and likely variety. Instruments can be passed down the colonoscope to sample the polyp or remove it. Small polyps can be pinched off with a pair of forceps, and larger polyps can be removed by passing a snare over the polyp and tightening it beneath the polyp to the point of amputation of the polyp. This is a totally painless process that you will not feel. If the polyp is a little larger, the doctor may apply electrical current called cautery to the polyp to seal it off as the polyp was removed. A very large polyp may need to have fluid injected beneath it, an injection that you cannot feel at all. The polyp can then be snared in pieces. It is rare to encounter huge polyps that cannot be dealt with during a colonoscopy. These have to be removed surgically subsequently.

Once a polyp has been removed, it is sent for analysis. The pathologist gives us a full report on the type of polyp and the presence of any dysplasia within it. You will then be advised on when it would be prudent to reattend for a checkup colonoscopy. If you have a large polyp with worrying features within it, you will be recalled for a checkup quite early e.g. 6 months to 1 year. Similarly, if you were found to have lots of polyps we may elect to bring you back a little sooner e.g. 1 to 2 years. If the polyp types are friendly, small and few in number, the interval for a checkup could be 3 to 5 years.

If you have produced an unusual number of polyps, or a number of more worrisome polyps, or there is a strong family pedigree of polyps and cancer, then you might be offered a referral to the New Zealand Familial Gastrointestinal Cancer Service. This service keeps a national registry of people at risk of digestive system cancers and they can investigate your DNA profile to advise you and your wider family members of whether to have screening colonoscopy and when they should commence this.