Our New Zealand population has one of the highest bowel cancer rates in the world already, with the average Kiwi facing a one in sixteen (1:16) chance of being diagnosed with bowel cancer in their lifetime. Having a family member with bowel cancer makes that risk even higher. Bowel cancer – also known as colorectal cancer (CRC) – has traditionally been more prevalent among older adults and many younger adults feel somewhat immune to this affecting them personally. Screening for bowel cancer has typically only targeted the over 60’s. However, recent studies indicate a concerning rise in early-onset bowel cancer globally. This rise in cancer amongst younger adults has been dramatic in the last two decades and should be a wake-up call to any adult Kiwi, of any age, who has bowel symptoms or who has a family member who has had polyps or bowel cancer.

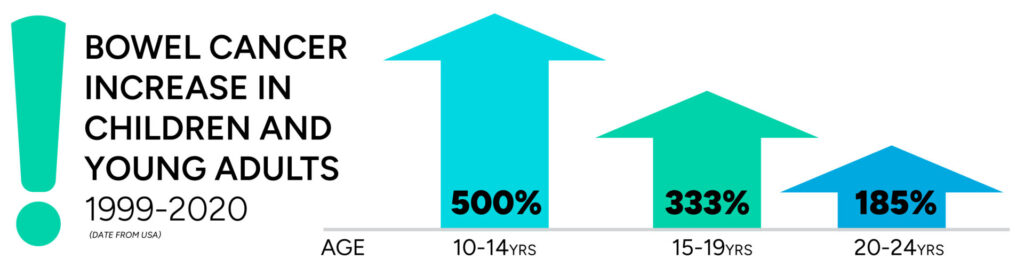

Early-onset bowel cancer, defined as bowel cancer diagnosed before the age of 50, has spiked recently. Between 1999 and 2019, early-onset cancers—those diagnosed in people younger than 50—increased by nearly 15% in the USA, according to the National Cancer Institute. Americans aged 20 to 29 experienced a 7.9% annual rise in bowel cancer cases between 2004 and 2016, and those aged 30 to 39 saw a 3.4% annual increase during the same period. Europe mirrors this concerning pattern. A comprehensive study across 20 European countries reported an approximate 8% annual increase in bowel cancer cases among individuals in their 20s, a 5% rise among those in their 30s, and a 1.6% increase among individuals in their 40s over a decade. Researchers in an earlier study found that bowel cancer has increased by about 2% per year in people younger than 50 since the mid-1990s. A person born in 1990 has quadruple the risk of developing colorectal cancer at a given age, compared to someone at the same age who was born in 1950. In New Zealand, the trend amongst younger adults is similar. We began to see this as far back as the mid-1990’s: From 1995 to 2012, early-onset rectal cancer in New Zealand men increased by 18%, and by 13% in New Zealand women during that period. Between 2000 and 2020, there were 56,761 cases of bowel cancer diagnosed in New Zealand of which 3,702 (6.5%) were in the under 50’s. For those under age 50 we saw the bowel cancer incidence rising from 4.41 per 100,000 in 2000 to 8.03 per 100,000 in 2020, an average increase of 26% per decade. The study also highlighted disparities among different ethnic groups: Māori individuals exhibited higher incidence rates compared to non-Māori, with an age standardised rate of 9.1 versus 6.9 per 100,000, respectively.

Being diagnosed with bowel cancer at any age is awful, but being diagnosed young or too late is tragic. It is, after all, a largely preventable and curable disease. Younger patients often present with advanced disease stages at diagnosis, because they are slow to report their symptoms or they get ignored by doctors when they do. This makes their bowel cancer less likely to be cured and they can face much more arduous treatments, like chemotherapy or radiotherapy, than if they had been diagnosed earlier. More than 90% of people treated for early-stage bowel cancer are alive five years after diagnosis, but that number drops to 15% or less once the disease has spread to distant organs beyond the colon or rectum. The double jeopardy comes from the impact that this has on families and communities. Younger adults are breadwinners, they are taxpayers, they are your team mates, they are business owners, they are critical workers and they are providers – to their own children and often to older parents too. The impact of a bowel cancer diagnosis on a younger adult reverberates throughout their family and their community much more so than it does when someone of advanced age is diagnosed.

Being diagnosed with bowel cancer at any age is awful, but being diagnosed young or too late is tragic. It is, after all, a largely preventable and curable disease. Younger patients often present with advanced disease stages at diagnosis, because they are slow to report their symptoms or they get ignored by doctors when they do. This makes their bowel cancer less likely to be cured and they can face much more arduous treatments, like chemotherapy or radiotherapy, than if they had been diagnosed earlier. More than 90% of people treated for early-stage bowel cancer are alive five years after diagnosis, but that number drops to 15% or less once the disease has spread to distant organs beyond the colon or rectum. The double jeopardy comes from the impact that this has on families and communities. Younger adults are breadwinners, they are taxpayers, they are your team mates, they are business owners, they are critical workers and they are providers – to their own children and often to older parents too. The impact of a bowel cancer diagnosis on a younger adult reverberates throughout their family and their community much more so than it does when someone of advanced age is diagnosed.

What might be going on?

With very few exceptions, bowel cancer arises from a benign bowel polyp growing in the colon or rectum. Without polyps, you generally don’t get bowel cancer and what makes someone grow a polyp boils down to your genes and their DNA. Every day our DNA codes a message, or program, deciding how a bowel lining cell should behave. It’s a bit like running the software on your computer – it tells various applications how to run programs.  DNA code can get flaws in it, either inherited flaws from our parents and their predecessors, or acquired flaws because of the influence of harmful factors damaging our DNA code. This flaw in the code allows our bowel lining cells to “go rogue” and multiply to become a polyp. Further flaws can then also influence the tendency for that polyp to transform into a cancer, or even for the cancer to spread elsewhere. So why then are we seeing the rising trends in bowel cancer in young adults?

DNA code can get flaws in it, either inherited flaws from our parents and their predecessors, or acquired flaws because of the influence of harmful factors damaging our DNA code. This flaw in the code allows our bowel lining cells to “go rogue” and multiply to become a polyp. Further flaws can then also influence the tendency for that polyp to transform into a cancer, or even for the cancer to spread elsewhere. So why then are we seeing the rising trends in bowel cancer in young adults?

The answer probably lies in these harmful environmental factors that are damaging the DNA of our bowel lining cells. We call this ‘Epigenetics’ – the manipulation of our genes by environmental factors. We have long known of other Epigenetic factors, like smoking, nitrates and the aging process itself. For younger adults it does not seem to be aging or smoking, but it probably is down to some important differences between the older generation and the younger generations: obesity, more sedentary lifestyles, highly processed foods, Western diet, higher red meat consumption, greater use of preservatives, growth hormonal manipulation of livestock, sugar consumption, lower fibre consumption, alteration to the gut’s microbiome (balance of organisms) within us and perhaps even microplastics. This area of research is on-going.

What can you do?

A popular public awareness campaign for bowel cancer ran the headline “Don’t die of embarrassment”. That is a large part of the solution – overcoming one’s embarrassment to talk about bowels and your poop, and the embarrassment of being examined somewhere rather intimate by a doctor. If you are having symptoms from your bowel, or if you have been fatigued and found to be anaemic, don’t blame it on middle life fatigue or heavy periods – get a conversation going. Similarly, if you have a family pedigree of either bowel polyps or bowel cancer, have a conversation with a doctor who understands that age DOESN’T MATTER, that family bowel cancer genetics ARE relevant and that Epigenetics are an increasing risk to you. Current American guidelines recommend a colonoscopy screening for everyone at age 45 – even if you have zero symptoms and no family history. Don’t procrastinate and don’t take “no” for an answer if your concerns are too easily dismissed. If in doubt, seek me out.